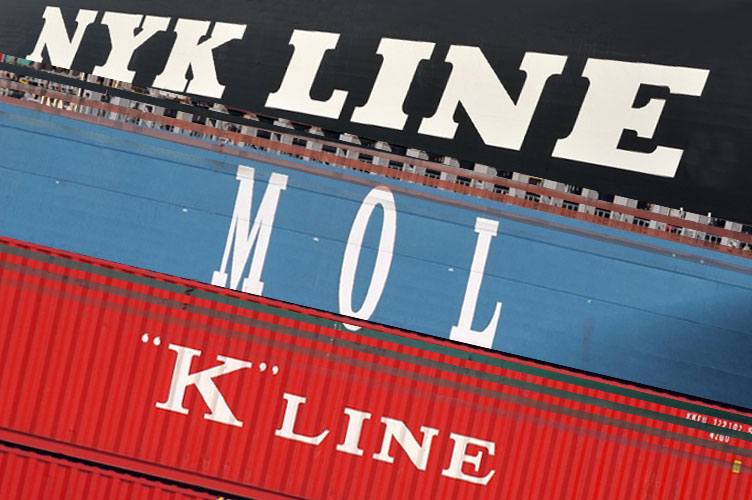

Japanese Shipping Line Merger

Three Japanese shipping lines, NYK, MOL and K Line have announced the new name of their merged containership entitiy: Ocean Network Express (ONE) and have confirmed that their new venture will commence as of 1 April 2018 pending anti-trust reviews. A holding company is to be set up in Tokyo, with global offices in Singapore, and regional offices in Hong Kong, London, Virginia and Sao Paulo.

When ONE becomes operational it will be the world’s sixth largest carrier when measured by containership fleet, with close to 1.4 million TEU, giving it a market share of approximately 7% based on today’s fleet. Under the terms of the joint-venture agreement, NYK will be the largest shareholder with 38%, while MOL and K Line will both have 31%.

Over the past five years, MOL had the largest container-related revenues of the three, generating calendar-year sales of $33.5 billion since 2012. Over the same period NYK and K Line each had container sales of approximately $29bn. Between them, the ONE carriers have seen annual container sales diminish by around 20% since the 2014 peak of $20bn to $15.7bn in the calendar year 2016. Since 2015-2017 the three lines have suffered a total of $1 billion in collective operating losses from container operations, therefore it makes sense that the lines come together to seek the cost savings and reverse their fortunes.

The creation of ONE is keeping up with the rising trend of consolidation within the container industry. If things continue on track, by 2021 when all new ships are due to have been delivered, the top five carriers will control a little under 60% of the world’s containership fleet. Back in 2005 the same bracket of carriers held around 37%. Come 2021 the top 10 lines will control 80% (55% in 2005) of the market.

The consequence of all of this is that shippers have fewer options to choose from. It is the unfortunate price that has to be paid for years of non-compensatory freight rates that have driven carriers to seek safety in numbers, either through bigger alliances and/or mergers and aquistions. The number of vessel operators on the two biggest deep-sea trades, Transpacific and Asia-North Europe have reduced significantly over the past two years. As of June 2017 there are only nine different carriers deploying ships in Asia-North Europe, compared to 16 in January 2015. In the Transpacific, the number has reduced from 21 to 16 over the same period. Shippers can also call upon non-operating slot charterers on a service-by-service basis, but there is no question that the pool is getting much smaller, therefore handing greater pricing-power over to carriers.

When ONE becomes operational it will be the world’s sixth largest carrier when measured by containership fleet, with close to 1.4 million TEU, giving it a market share of approximately 7% based on today’s fleet. Under the terms of the joint-venture agreement, NYK will be the largest shareholder with 38%, while MOL and K Line will both have 31%.

Over the past five years, MOL had the largest container-related revenues of the three, generating calendar-year sales of $33.5 billion since 2012. Over the same period NYK and K Line each had container sales of approximately $29bn. Between them, the ONE carriers have seen annual container sales diminish by around 20% since the 2014 peak of $20bn to $15.7bn in the calendar year 2016. Since 2015-2017 the three lines have suffered a total of $1 billion in collective operating losses from container operations, therefore it makes sense that the lines come together to seek the cost savings and reverse their fortunes.

The creation of ONE is keeping up with the rising trend of consolidation within the container industry. If things continue on track, by 2021 when all new ships are due to have been delivered, the top five carriers will control a little under 60% of the world’s containership fleet. Back in 2005 the same bracket of carriers held around 37%. Come 2021 the top 10 lines will control 80% (55% in 2005) of the market.

The consequence of all of this is that shippers have fewer options to choose from. It is the unfortunate price that has to be paid for years of non-compensatory freight rates that have driven carriers to seek safety in numbers, either through bigger alliances and/or mergers and aquistions. The number of vessel operators on the two biggest deep-sea trades, Transpacific and Asia-North Europe have reduced significantly over the past two years. As of June 2017 there are only nine different carriers deploying ships in Asia-North Europe, compared to 16 in January 2015. In the Transpacific, the number has reduced from 21 to 16 over the same period. Shippers can also call upon non-operating slot charterers on a service-by-service basis, but there is no question that the pool is getting much smaller, therefore handing greater pricing-power over to carriers.